On July 18th, GLC Education & Outreach Coordinator Paul Baines gave a workshop in Cambridge Ontario about our relationship with water. Based on the 2017 Water Friendship pilot project, this event was part of the Common Waters project:

Common Waters is a community project that examines our relationship with water and provides a platform for us to discuss some of the most pressing issues of our time. This project explores diverse artistic, scientific, cultural, and personal perspectives through a curated sequence of art installations, workshops, discussions, gatherings, and excursions. These activations provide a platform for considering our shared waters through the lenses of environment, identity, history, and sustainability.

Hosted by BRIDGE (Waterloo School of Architecture, the University of Waterloo) and the Cambridge Art Galleries, this project surrounds the Grand River from June 14 to September 15, 2019.

It started with three reflections about how we think:

We can not solve a problem with same kind of thinking that created it.

We count and name what matters to us.

If all you have is a hammer, then nails are what you go looking for.

What kind of thinking is most at play when it comes to water protection:

We have inherited a world of dead resources, useful animals, and entitled humans.

Measuring water quality and reporting its pollution will prompt collective action.

What do we count and name? The Water Friendship project was inspired in part by the Canadian Index of Wellbeing. Attempting to provide indicators of wellbeing rather than the growth of the economy — Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the CIW looks at key factors within 8 categories:

community vitality

democratic engagement

education

time use

healthy populations

leisure & culture

living standards

environment

What stood out for Paul Baines was the lack of ‘relational’ indicators for the Environment category (unlike the rest). The Water Friendship project set out to ask “what does a good relationship with water look like?” and how could these patterns inform policy, education and advocacy that works with a ‘different kind’ of thinking?

We have many well researched indicators for water quality, but what about the quality of our relationship to water? We have ‘named’ our environment/water issues as ones of ‘resources’, ‘assets’, ‘h2o’, and ‘services’ and in return we have excellent methods for collecting knowledge about water’s quality and quantity (ph level, dissolved oxygen, chemical composition, cubic litres, etc). A relational indicator would be looking at the connection between 2 or more parts, rather than things in isolation.

The CIW has found ways to measure these connections and relationships for the other categories, but not or the environment category. For instance, it counts:

Average visitation per site to all National Parks and National Historic Sites (Leisure and Culture)

Ratio of students to educators in public schools (Education)

Amount of time spent in talk-based activities with children aged 0 to 14 years (Education)

Percentage of population that reports very or somewhat strong sense of belonging to community (Community Vitality)

Percentage of population that feels safe walking alone after dark (Community Vitality)

Percentage of population that is very or fairly satisfied with way democracy works in Canada (Democratic Engagement)

Percentage of population that rates their overall health as very good or excellent (Healthy Populations)

Average daily amount of time with friends (minutes per day) (Time Use)

It’s also interesting that the worst performing category for the CIW was ‘the environment’. When we look at the hundreds of impacts and threats to the Great Lakes for instance, it becomes clear that by only counting and naming water quality and quantity, we are missing critical knowledge about our relationship to water that is currently killing these lakes and yet has the potential heal them.

Robin Wall Kimmerer writes about our relationship not only with ‘the environment’ but with the language we use to understand what ‘the environment’ is. In this article, she writes:

Imagine your grandmother standing at the stove in her apron and someone says, “Look, it is making soup. It has gray hair.” We might snicker at such a mistake; at the same time we recoil. In English, we never refer to a person as “it.” Such a grammatical error would be a profound act of disrespect. “It” robs a person of selfhood and kinship, reducing a person to a thing.

And yet in English, we speak of our beloved Grandmother Earth in exactly that way: as “it.” The language allows no form of respect for the more-than-human beings with whom we share the Earth. In English, a being is either a human or an “it.”

The premise of the Water Friendship project is that we need to return to an Indigenous way of naming and counting our water strategies. When searching for an image of ‘the water cycle’ we see the common one below. The closest way we have to describing these complex relationships is with directional arrows. Ironically, there are no people or animals in this water cycle. Designing water advocacy strategies that can’t understand relationships better than arrows and missing elements continues a pathway of failure.

In this Common Waters workshop, we started seeing the world as a matrix of relationships. To practice, Paul showed sets of words and asked people to describe the relationship between the words.

car / road

summer / winter

hunger / food

Cambridge / Grand River

water / life

lock / key

It is a simple and mostly obvious exercise, yet we continue to address water issues from the perspective of the parts, rather than the partnerships. This separation blinds us from the root causes of water pollution and privatization since we currently have an ‘ego’ relationship with water and ‘the environment’ but we overlook this core teaching when searching for water data.

In the same article, Robin Wall Kimmerer continues to teach us about the power of language and relationship:

Colonization, we know, attempts to replace indigenous cultures with the culture of the settler. One of its tools is linguistic imperialism, or the overwriting of language and names.

Among the many examples of linguistic imperialism, perhaps none is more pernicious than the replacement of the language of nature as subject with the language of nature as object. We can see the consequences all around us as we enter an age of extinction precipitated by how we think and how we live.

At this point in the workshop we heard from each person on the question “what is your relationship with water like"?”

We heard a range of replies spanning very connected and mindful to very abusive and mindless. Several in the group had never considered such a question while knowing that local water is the basis of their life and wellbeing.

Paul introduced the Water Friendship project as a response to the teachings and gaps illustrated above. Read all about it in our summary report. The key points were:

What does a good relationship with water look like?

Water protector participants in Guelph, Peterborough, and Thunder Bay.

What are the patterns/signals/indicators for this good relationship?

What are the key teachings we need to understand the basis of this relationship?

Communities initiated local projects that animated this friendship.

While the pilot project didn’t result in a new framework for mapping out the kinship relationships we have with water, it did create 9 key teachings that can anchor the basis of these relationships.

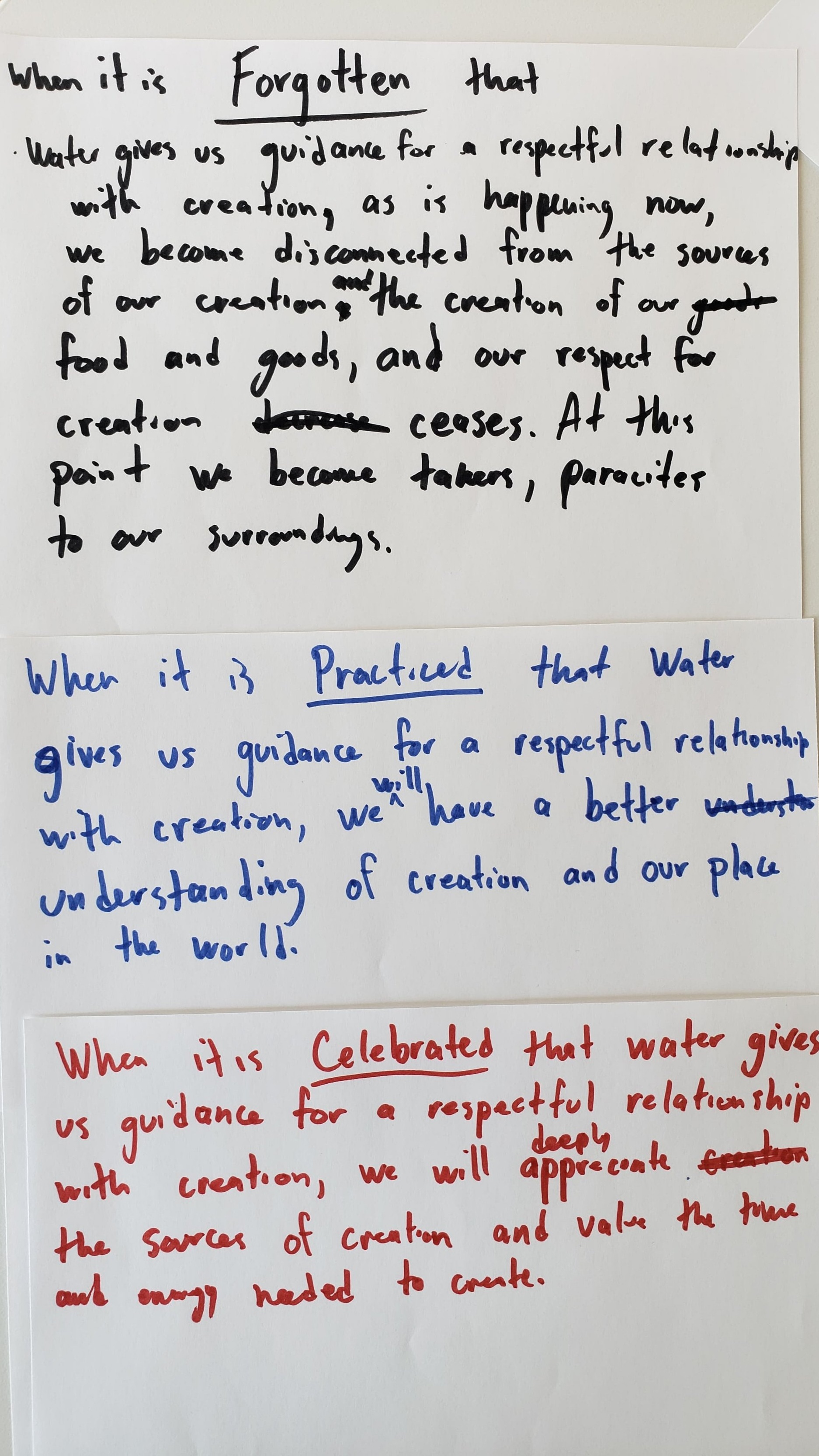

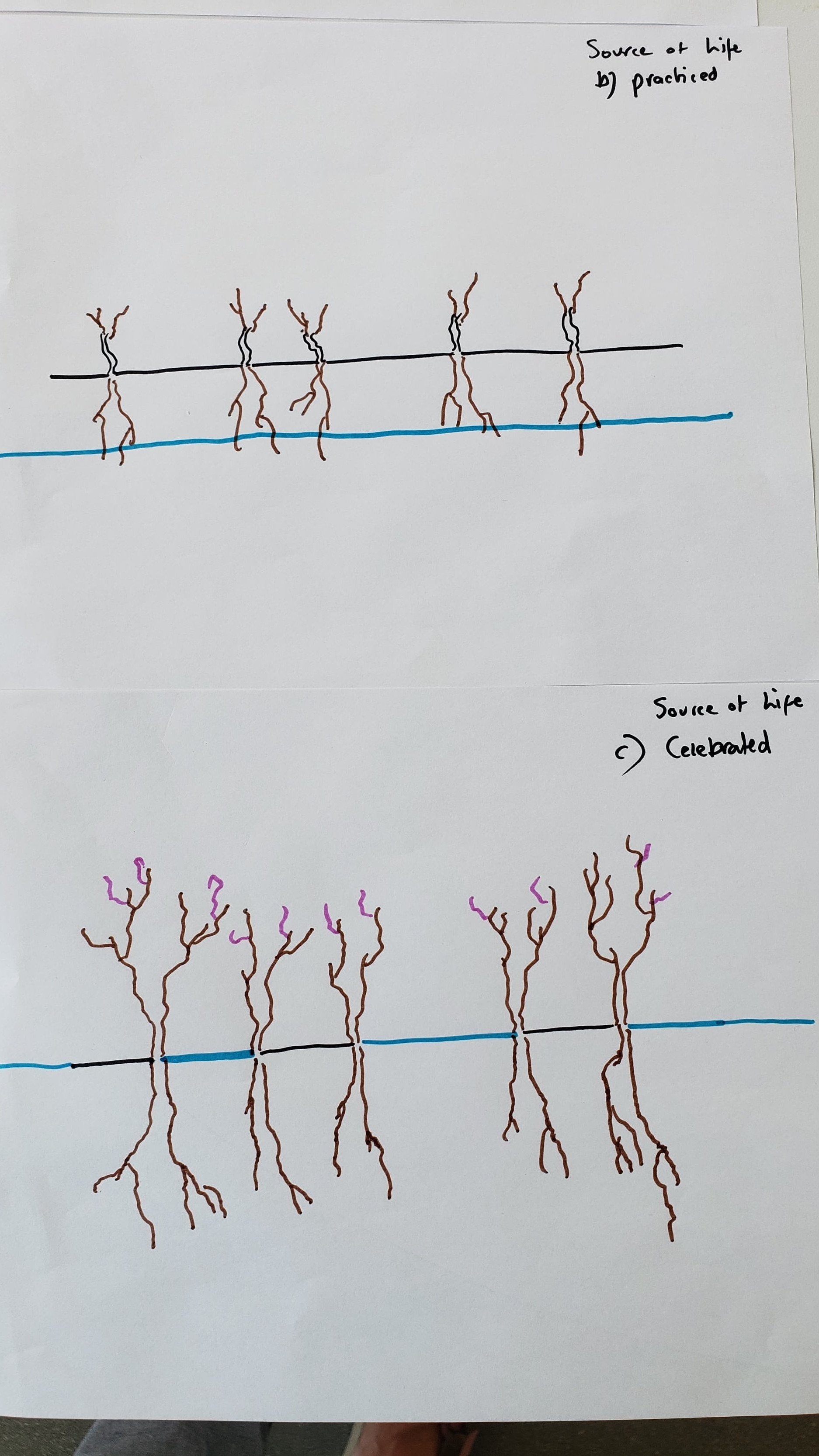

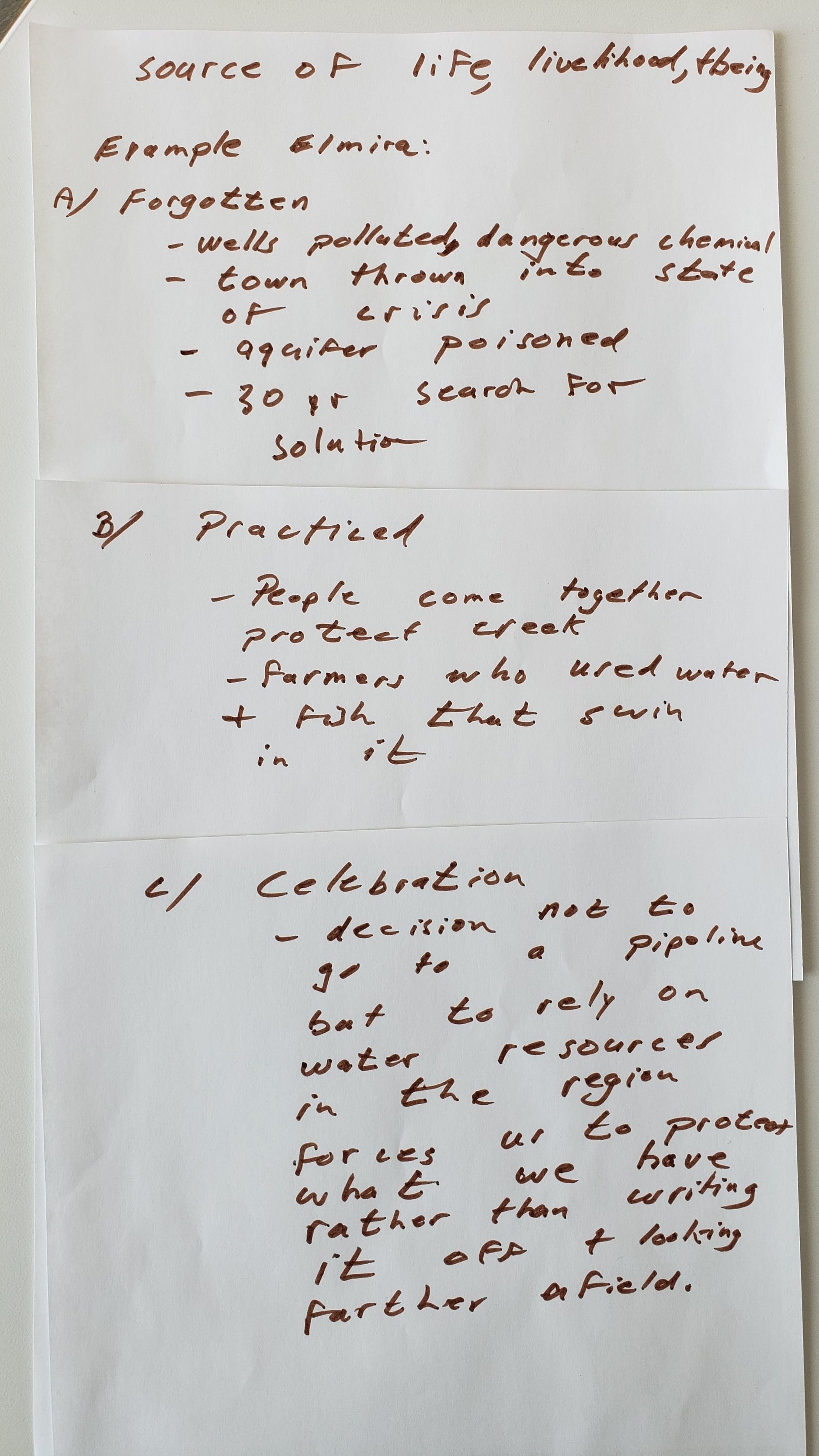

After discussing a few of the teachings that people were curious/confused about, it was the participant’s turn to help create these relational patterns/signal/descriptions of what a good relationship with water can look like. People were asked to:

Pick 1 or 2 Water Friendship teachings that resonated with them.

For each teaching, use the paper and markers to describe what is happening when this teaching is a) forgotten b) practiced c) celebrated

Use different sheets of paper and different colours for a/b/c descriptions

The word ‘forgotten’ was used here to indicate that we all have Indigenous ancestry and ways of relating to the non-human world — we have just lost this knowledge and experience. ‘Practiced’ examples would be ones were we start to see a portion of this teaching present in the world, but still on the periphery. ‘Celebrated’ examples are when this teaching is adopted and supported by the broader society and fused within its stories, institutions, laws, and shared identity.

After about 15 minutes, each person shared their examples as well as reflecting on the experience of making the examples.

People often saw the ‘forgotten’ example as a reflection of what is currently going on and was generally easier to describe or draw. The ‘practiced’ and ‘celebrated’ examples were more aspirational for the future, took more time to name, and were sometimes at play right now in our daily lives or for special events.

For instance, when we are happy when the rain falls and when we talk ‘to’ rather that just ‘about’ our tomato plants we are engaged in a water friendship.

When we see ourselves as givers and not just takers, our water relationship improves.

When we know the sources of water’s pollution and desire the fish that the river could once again provide, we find our source of connection.

When we change our language to be less possessive (our water) and less utilitarian (swimmable, fishable, swimmable), we can more fully embrace water’s many gifts.

When we see past state borders and start to ground our politics within shared watersheds, we are respecting the lessons of water.

Common to many examples were the values and practices of respect, belonging, gratitude, love, healing, sharing, and understanding — a true basis for friendship.