The Erie Effect

What good is art in the face of ecological tragedy?

That might not be the most fruitful lead; let me come at it from another angle.

The Erie algae blooms are smaller this year than last. Some might see in this news a sign of progress: Toledo’s drinking water shouldn’t be cut off this summer (at least not for environmental reasons). But the myth of progress, the story that things in this world are getting better, dissipates, it seems, the deeper you dive into its waters, or the farther out of them you rise.

I read from a Traverse City-based non-profit Circle of Blue (COB) that a major reason the blooms are registering at nearly half the severity as last year has less to do with a reduction in phosphorous-and-nitrogen-rich agricultural runoff (there’s been no such reduction), and a lot more to do with drought.

If you watch the weather, you may have noticed over the rustbelt the skies have been conservative with snow and rainfall—evidence the brown lawns and sprinklers. Less rain means less runoff; less runoff means less GMO food for the blooms. The problem has not been solved—industrial farms are still dumping liberal amounts of nutrient-rich fertilizers, accounting for over 85% of phosphorous runoff. The problem has only shifted with the climate.

A mini-drought has its own consequences, negative for most water bodies, especially the industrial farmers who desperately want water to do things like grow food. Just as a rising tide does not lift all boats, a receding tide does not drop all priorities.

So what good is art in the face of ecological tragedy?

The problem-solvers—in this case, Michigan Governor Rick Synder of the 2016 Flint Lead Disaster and Ohio Governor John Kasich of the 2016 Republican Primary Disaster, as well as Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne—have no need for artful ways of knowing when statistics will suffice. They have, without input from the people of the lakes, designed a plan to reduce phosphorous flows into Lake Erie by 40% in the next nine years, COB reports. This ambitious plan calls for the planting of cover crops and wild (“uncultivated”) grassland to catch the rain runoff and filter out the fertilizers. The buffer crops store the excess phosphorous and nitrogen in their roots, turning it into salubrious soil.

Here’s the kicker: these buffers of wildness would require the conversion of half of existing farmland. Half. The agricultural industry does not need artful ways of knowing to call this plan unrealistic.

Still, buffers are on the table. Some may see in this proposal a sign of progress. What’s not on the table is cutting out the dumping of chemical fertilizers all together, or at least by half. Solutions, it seems, are on offer, as long as we do not have to face the sources of the problem.

Herein lies the Erie effect: lake eutrophication as toxic algae blooms, a year-in, year-out industrial production of dead zones, with only buffers to slow the death. The blue-green algae, it turns out, is a great symbol of our Erie cities: growth as bloom.

The Erie effect is becoming, increasingly, an unbearable situation in our gentrifying cities, a pattern emerging across North America metropolises: shallow, overfed, and, with the stubborn persistence of tour buses and pedal pubs as examples of floating dead zones, toxic.

In 2002 a rural-French journal called Tiqqun articulated this deadening effect in western society as the theory of bloom, “as the sad product of the time of the multitudes, as the catastrophic child of the industrial era and the end of all enchantments…what’s left is the necessary anxiety we think we can appease by demanding of one another a rigorous absence from each other’s selves, and an ignorance of a force which is common, but is now unqualifiable, because it is anonymous. And the name of that anonymity is Bloom.”

A rigorous absence. We work hard to make strangers of each other, repressing a natural tendency to ask a fellow human being on the sidewalk for directions instead of asking Google, to strike up a conversation at the counter instead of swiping left, to initiate a game of tag in a park without premeditation or virtual reality interfaces; we work hard to repress a tendency to common.

We want solutions to our problem of depression—nano-breweries and pour-over coffee, down or up, either way, get me out of this funk! -- as long as we don’t look at the source.

But where are we to look? And who’s looking back?

Art as Buffer

I still want to ask it, so I will. What good is art?

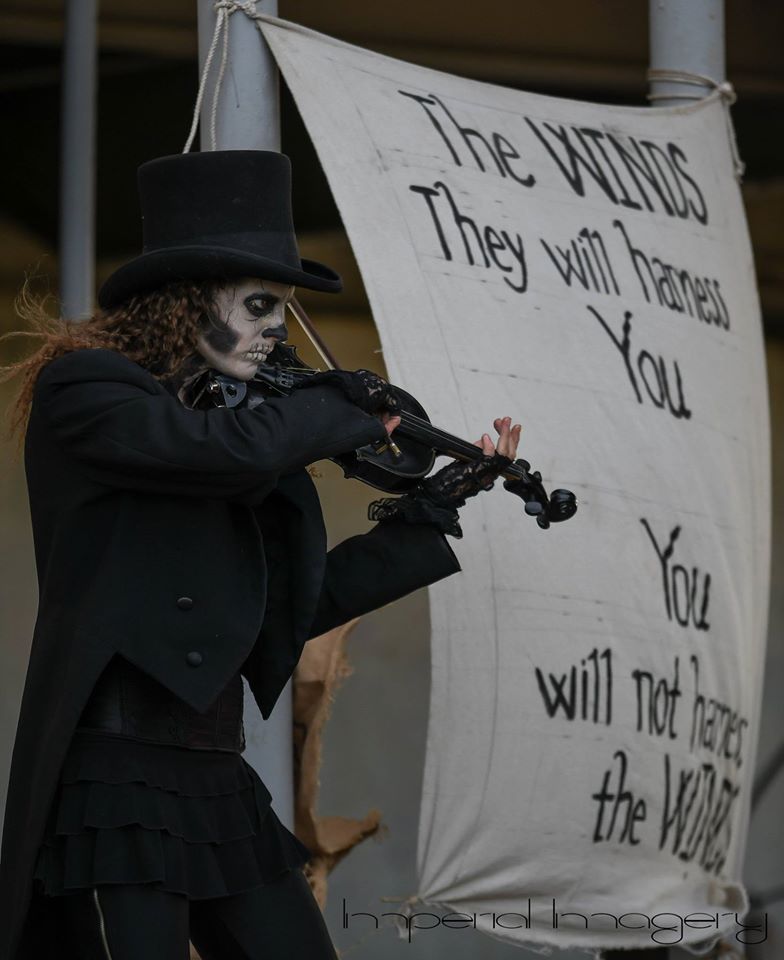

I confess: this question stems directly from a review of The Wastelands by an audience member at our Cleveland performance in St. John’s Church. Aaron Rutz, an ensemble-theatre practitioner himself, watched our Saturday show and came back for Sunday, writing a piece that opens: Is art necessary?

He goes on, careful not to answer, “It was a question of synthesis, there is so much at play in the company’s work, so much power that it must be asked when does a performance saturate and when does it overwhelm?”

We are overwhelmed with police killings and fractured attention and hateful comments and traumatic stories and loveless relationships. Overwhelmed with work and fear and noise and mental pollution. Our industrial society is producing a lot of shit. No wonder The Wastelands whelms over. The project itself is overwhelmed by the source material.

In such a society, art, I’m starting to think, can act as the wild grass, the buffer that soaks up the shit and processes it, some of it, synthesizing it into a form that can give back to the soil of our communities, preventing that shit from running unfiltered into the basin that is life. Our art, like our wastelands, is an ambitious proposal to convert our shit into nourishment, that is, into meaning.

Our Cleveland testimonialist, poet RA Washington, speaks from his Body to the place of meaning, an artful pattern from trauma to compassion: “Why does it not seem odd to us that when our mothers pass away, whenever this inevitability occurs, only then can we identify that grief in others?” This is a good question. What is the source of this inner emptiness, this loneliness, this “delay”, this “secret pact to not disclose”? What is the source of this bloom?

Theatre, like any buffer crop, does not stop the trauma; it only cultivates meaning out of it. Meaning, Barthes says, RA says, grows, develops, causes suffering, and passes away. That is the pattern. Like soil built up from composted waste, meaning does more than lessen blooms; it yields its own fruit.

That’s how I arrive at this question, what good is art? Looking at The Wastelands Project as a buffer between the trauma of our industrial world and life, I’m still faced with the question of what to face. Where is all this shit coming from?

Why does it matter how powerfully we perform, when we are only acting as buffers? The police keep killing and love seems to slip further away. We are not the source. And sooner or later, the rains will fall hard again, and wash that trauma our way again.

At this point, I’ve had nights to reflect on these questions, reflecting on the waters. I think of our Cleveland collaborator and Great Lakes Commoner Kathy, who asks, when she gets a chance, “when you look at the water, who looks back?”

Standing on the shores of Lake Erie in Lorain, OH, just west of Cleveland, I look into the lake. I don’t see my reflection looking back. And I don’t see the blooms. I see mussels. I see pearly whites.

And I see it all recede.