“We organize around the seeds of the trees under which we want to live.”

So says Ricardo Levins Morales, organizer of organizers, an artist who has been cultivating, among other seeds, the Great Lakes Commons ever since the grassroots movement was planted in 2011. He says this, as a matter of business, over a GLC visioning call from his home in Minneapolis. We are in Petoskey, a crooked tree town on Little Traverse Bay of Lake Michigan, trying our best staying in touch with the people behind the movement we want to enter.

While I was still in the foothills of western Mass I saw Chuck D lecture at a college for three hours on the topic of life. The organizers gave him a mic and just set him free to spit wisdom. At one point he said, to understand someone you have to stand under them. Stand under. Those words have been sprouting in me ever since. And now, from across the region, Ricardo has watered, in his knowlingly unknowing way, the roots of this idea.

The Wastelands Documentary until now has largely focused on the relationship between our art and social organizing. I had been up till now looking at patterns of commoning in the wastelands—not in the abstract, but through concrete particulars. I’ve been looking at patterns of infrastructure, private development, creation of art, legacies of waste, patterns of resistance and resilience in environments of industrial decay. I haven’t been looking at the trees that provide habitat for it all, trees that make these environments, trees that took root long ago, trees that are just being planted now. How do we, how do I understand the commons by understanding the trees? What do we want to stand under?

Something tells me the answer is somewhere in the palm of my hand. I think there’s a connection, hidden no doubt, between the land itself—as in the interdependent kingdoms of plant and animal, fungus and protozoa, not to speak of the single cells—and the maps that purport to point it all out. I think my body—sovereign, broken—contains all the info I need to identify the outer nature of these kingdoms, because I can feel these kingdoms in my inner nature.

The truth is I’ve always been a poor student when it comes to identification, plant and otherwise. It’s not that I don’t appreciate attention to detail. In fact, it’s the attention to detail that messes me up. I find identity problematic. Who am I anyway? I know, for example, a linden tree that has more in common with the birds it knows than other lindens of its type, so much so that this tree is a bird. But that’s another story. Let me circle back to Ricardo. It’s a windy path, full of shady trees, but such are roads worth traveling.

Little Traverse Bay

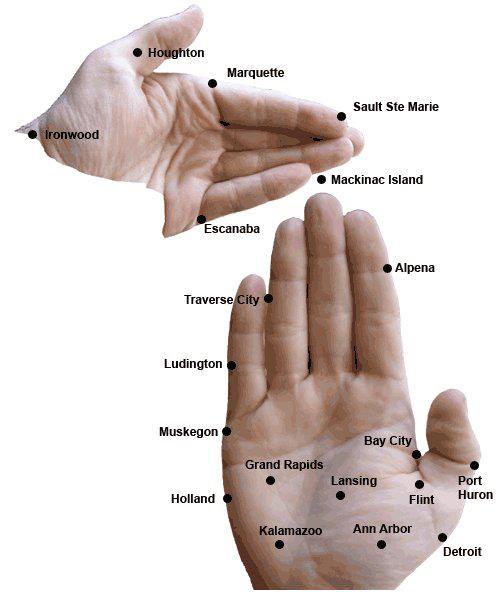

(tip of the ring finger)

I think it’s curious that we all have a map of Michigan, and no other state, with us at all times. Put up your hands, palms facing you. Your right hand is the Lower Peninsula, which is why they call it the Mitt. If you were to make the shape of a finger gun with your left hand, which, who doesn’t like to do that? you’d have a rough map of the Upper Peninsula. It’s a handy device when you’re trying to place the geography of a story.

The Wastelands Documentary is following a different track than the one I set out to trace, an other track. The places we film are shaping the story in ways I could not know beforehand. We schedule an interview, for example, in Harbor Springs, a small community on the north shore of Little Traverse Bay just north of Petoskey. The shape of the lake here has given rise to certain trees, and certain trees have shaped certain thoughts.

I point to the little nook between to my ring and middle fingers to get you oriented. We meet with Paul Baines, animator of Great Lakes Commons, and together drive to the house of Frank Ettawageshik, an “elder in training” and “recovering Tribal Chairman” of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians.

To list Frank’s accomplishments is a practice in endurance. I ask him how many boards of organizations he is a part of. Oh, just eight, he chuckles, a chuckle that communicates it has been many more over the years. Frank is currently the Executive Director of the United Tribes of Michigan and last year represented the indigenous of North America—all of North America—at the United Nations COP21 Climate Change Conference in Paris. He makes it painfully clear that, as he talks to us, he does not represent anyone but himself. Frank is not the Odawa people. Frank is Frank.

Frank, being frank, is an unlikely rebel. Soft and generous in conversation, he speaks swiftly and deliberately like a tree that suddenly forks to mark a secret trail that many passersby do not have eyes to see.

He guides us into his backyard, past an ancient maple tree, to a lodge he built himself, where we set up to film. Lingering for a moment under the sanctuary of this 300-year-plus maple, my mind finds breath enough to whisk me off to faraway lands, where stories pop up like unnamed berries in some patch of shady grass.

In his Book of Imaginary Beings the blind poet Jorge Luis Borges complies a long list of mythical creatures across cultures and time. Somewhere in the middle of this curious book Borges writes of the Lamed Wufniks, meek beings whom he describes as very poor and who don’t know each other. According to Borges there exist precisely 36 Lamed Wufniks on Earth at any one time. Their mission, of which they are completely unconscious, is to justify humanity to the rest of God.

I think Frank is a Lamed Wufnik. Secretly holding up a corner of the universe, he would never know it, because once a Lamed Wufnik becomes aware of their being, they at once die and someone else takes their place.

For the last year we’ve been talking, off and on, Frank and I. Well I’ve mostly been listening, to tales of the inner congressional workings of Great Lakes governance, to the cop-outs of global climate agreements, to the natural history of northern Michigan, to stories of sturgeon, little people, and homesickness. “What you have to do”, I remember Frank telling me on one of our pre-tour phone calls in his gentle, froggy tenor, “is set aside four hours of your time in Michigan to sit on the shores of the dunes and look out at the water. If you don’t schedule it, it won’t happen.”

Which reminds me of how we got here under the shade of this maple tree in the first place.

Empire

(top knuckle of the pinky)

Since we started this journey, we’ve been in cities, where the infrastructure and the people it shapes have turned theirs backs on the waters. Our time in Michigan is scheduled for us to be facing the water, to reconnect with the original source of inspiration for this adventure.

We run with Frank’s advice, setting aside four days, not four hours, to camp and commune with some of the wildest nature western Michigan has to offer. On the fourth day of our time in the Sleeping Bear Dunes—a 35-mile stretch of designated National Lakeshore that claims the hearts of tourists and tourist boards across America—we meet with another soft-spoken guide, Luke Evans of Traverse City, who guides us to one of his favorite spots in the area. Luke is a recently-recruited organizer with Great Lakes Commons. Judging by his nonintrusive leadership style, I wonder, if not a Lamed Wufnik, what imaginary creature he might be. Like a Lorax with less ego. Turns out Luke has met Frank before; we’re not surprised. Accomplices tend to know each other on the outskirts of Empire.

Empire, in case you were wondering, is a small town on the west coast of Michigan in the heart of the Sleeping Bear Dunes. The bust of lumber has turned forests into visitor centers and the air force into museums, and in that sense Empire has faced the same fate as many former industrial towns in this country. The prevailing mood is as if only the tourist industry can save them now. Fitting that Empire would be slowing fading back into the forests from whence it came.

Luke takes us below Empire, down a shady path called Trail’s End Loop. It’s tempting to go off trail, to get lost in thick net of black cherry and white pine. Up ahead there’s a sign that reads THE DUNES ARE A FRAGILE ECOSYSTEM. Millennia of blowing sand, held, tentatively, by the grass. We stay on the trail so as not to make the grass’ job more difficult. Besides, there’s someplace we’re trying to be.

Mackinaw Bridge in the Straits of Mackinaw

This is not a pleasure hike. This is research.

The dunes are littered with baby’s breath and spotted knapweed, invasive to this land. Luke points to an unnamed endangered plant followed by an unnamed bird of prey. Why is it we can identify the problems so easily but not the sources of hope?

We don’t know the names of most things, which makes the conversation hard to hold. How do we identify our place in supporting native sovereignty? What does our research offer this quest? The hippies called it search, Double Edge calls it training, the situationists derive, insurrectionists whatever being, the mystics seek it through prayer and meditation, the dervishes through whirling, the hunters through hunting, the theorists through theorizing a western spirit against the wilderness, gardeners through composting, decomposition, I feel myself eroding the sand with every step we take, undoing the work of our ancestors, or someone’s ancestors. At least the grass and trees are holding it together.

There are known to be 185 nonnative species to have invaded the Great Lakes in the last 200 years. I read this in a book I later find in Luke’s house, titled, appropriately, The Great Lakes by Wayne Grady. Most of the native species by now have been starved out. I find it unsurprising that the most common form of entry for invaders is through the ballast of ocean-going ships. The story of industry is the modern history of invasion. Purple loosestrife, to pick an example at our feet, came over on ships from Eurasia as a garden herb and hidden in the wool of sheep. As soon as it hit New England, loosestrife’s spread was quick and devastating, traveling across the newly opened Erie Canal—designed as a passage for grains and goods from Buffalo to the Atlantic—choking out native grasses, sedges, flowers, and bulrushes, giving back no benefits to the marshes and lake edge habitats that provided them home. Which trees do we want to stand under? I’m still researching, but how many of them can possibly be nonnative? Which ones?

After an hour of sharing leadership on the trail we reach the water. Luke points out a small white mussel on the beach. Then we see another. And another. These are quaqqa mussels, he says. Or zebra mussels. Not quite sure. All these white bodies look the same to me. It’s a problem that I’m working on.

About thirty years ago, depending on whom you ask, zebra mussels first arrived in North America. This was summer that shifted the entire course of colonization on the Great Lakes. Zebra mussels have colonized certain niches earlier colonizers left open, and now the lakes have a hard time supporting any native life. They are bottom feeders, zebra mussels, taking over hard surfaces—rocks, piers, the hulls of ships, exposed pipelines, even other mussels. They reproduce at a catholic-rabbit rate, fuelling their insatiable sex drive by filter-feeding phytoplankton, gluts of it, nearly half their body carbon per day, which means no one on the Great Lakes—not the sturgeon, the pike, alewife, lamprey, not the piping plover, not the people bird watchers—could ever see it coming.

Their rapid growth and natural filtration means that the lakes’ waters are getting clearer. But as I’ve learned, clarity is not always a good thing. Clear water means more light penetration, and more sunlight means more green algae growth. As in, more blooms.

There’s more to this poisoned water-filter system. The phytoplankton that the mussels eat naturally sequester PCBs and other toxins. The hold it in and settle at the bottom. So when the mussels eat the phytoplankton, and then shit, they release these poisons into the food web, slowly turning the flesh of fish into heavy metals. I think of Virginia in Buffalo, of the PCBs leaching from the old General Motors plant across the street from her home, and I think of all the power and manufacturing plants we’ve come across so far—Marathon Oil, Enbridge Energy, American Axle—and of other invasive plants on the Great Lakes. These plants don’t give back what they take, and provide no lasting benefits to the communities that give them home. And yet, here we are—in Buffalo with GM, across the Midwest with Enbridge, back in Massachusetts with Kinder Morgan—organizing around the plants we don’t want to live under. Why is it so hard to organize around the plants we do want? How do we accept, with an awareness however unclear, the colonization that has come to dominate our world and yet recognize the seeds of the trees under which we want to live? How do we know what we want?

Let us return to Frank.

Straits of Mackinac

(nail of the middle finger)

“We all carry inside us the seeds of our destruction. We also carry the seeds to redeem ourselves.”

So says Frank during the final scene of The Wastelands at the Straits of Mackinac, standing between the Mackinac Bridge and the rapidly setting sun. He’s centered in front of the performers and our big metal tree, which is currently set about seven feet in the water from the shore. We carry the ability, Frank tells the audience—gathered around him like flowers under a maple tree—to realize we are all at one with the world, and yet we are not the center of it. Frank steps aside, when he is done delivering this testimony, and lets the waters speak for themselves.

Thirty miles up from Harbor Springs, the Straits of Mackinaw is known as an “area of high consequence”, an identifying marker for the pipeline industry when trying to determine how to skirt around existing ecological law, or as Michilimackinac, an identifying marker for the Odawa when determining the world’s crossroads. It all depends on whom you ask. This is where Lake Michigan and Lake Huron meet. How do you identify an area of “high consequence”? It’s on a state list, like an endangered species. Strange things happen at the Straits; they experience currents at times faster than Niagara Falls. It means that the seeds planted here travel far and fast and in crooked directions.

We organize this performance of The Wastelands at the McGulpin Point Lighthouse, on the Straits, in less than a week in order to redeem our otherwise research-heavy time in this area. A cadre of bikers have been biking the line from Detroit, tracing on bicycle the entire route of an Enbridge pipeline built in 1953 called Line 5 from its terminus in Sarnia, Canada to its starting point in Superior, WI, talking to homeowners along the route. Our performance in the Straits converges with their ride, and with a coalition called Oil and Water Don’t Mix, and with Paul of GLC, and with Frank. The Wastelands, I begin to see, is a movable metal tree around which we organize.

The performance location is an area of high consequence indeed. In between an Enbridge pumping station and the Straits themselves, we journey through a wasteland markedly different than the wastelands we’ve traveled before. The grounds surrounding the Lighthouse are manicured, the park monitored 24/7 by roving Enbridge security detail, the trail leading down to the water flanked by wooden cutouts of pioneers from the history of settlement, a landscape designed for tourists. At first glance we are entering a garden. But the wastelands through which we pass are not at all apparent; they lie beneath our feet. Underfoot lies Line 5, which runs along the floor of the Straits, exposed to the warping powers of the water. Recently an underwater camera crew released raw scuba footage of the length of Line 5. It’s covered in white mussels. And it’s buckling. The pipeline was designed to last 50 years. It’s been 63.

According to the company’s own records, Enbridge has caused over 800 pipeline leaks, between 1999 and 2010, including a spill on the Kalamazoo River in Michigan that dumped over 1 million gallons of dilbit (diluted bitumen) oil in what’s been the largest inland oil disaster in US history. You may have missed the Kalamazoo story. It came just months after another major oil spill. Deepwater Horizon.

If there were a spill on Line 5—of which there have already been plenty along its nearly 1,100 mile route—in the Straits of Mackinac, the tar sands oil, which is far stickier to clean up than conventional crude, would spread to both Lake Michigan and Lake Huron rapidly and irreversibly. In Michigan Line 5 is widely recognized as the seed of our destruction.

Liz Kirkwood speaks for a legal advocacy group based back in Traverse City called FLOW (For Love of Water). She is a dancing bear. The organization has been doing some extensive research and found that the 1953 Line 5 easement is held in public trust, by laws governing the commons, so if any private interest is doing something that threatens the Straits, Liz says, the State of Michigan is bound by duty to intervene. As of now the state has yet to shut down Line 5. But then again, this is the same state that has yet to replace Flint’s lead pipes.

It’s not easy to see we’ve been amongst all the medicine and protection that grows around us this whole time when looking at the state of things.

We continue on our crooked path down the state, to Flint, to Detroit. I’m beginning to look past the patterns of abuse and fear. I’m beginning to see what Ricardo is talking about when he talks about seeds. It’s not that we have to identify the trees we want to live under with a scientific clarity. We just have to see them, and give them water.

The U.P.

(left hand in the shape of a gun)

Part of me wants to get the state of Michigan tattooed on the inside of my right hand. That would make this story a lot easier to tell in person. But then people would think I’m from Michigan. I also think of our crooked metal tree. There’s an artist in Marquette, MI, named Graves who works at a tattoo parlor called Sacred. I might give him a call.