Special contributor: Emily Hines

A series of blog posts will focus on a critique of the Ontario Permit to Take Water Program (the Provincial legislation that allocates water taking permits, including municipal, private and bottled water incentives).

Why is this important?

Water takings have been occurring for over 100 years, with the first bottling permit established in 1912. In recent decades a surge in demand has allowed for an expansion in commercial water extractions throughout Canada – specifically centered in Southern Ontario and British Columbia.

Alongside this surge, the amount of water taken daily has also increased to a staggering rate at multiple plants; i.e. in 2011 Nestle applied for a permit to take 3.6 million litres per day for bottling purposes. This is nearly the size of 1.5 olympic-sized swimming pools of water being extracted everyday.

The Olympic Pool at the University of Toronto. Source: Stephanie Calvet at urbantoronto.ca

These epic rates of consumption, in addition to recorded increasing household consumption, are representative of a shift in the view of water as both a precious natural resource and natural gift, to that of a marketable commodity. This perspective, both echoed and seemingly preserved in provincial legislation is putting our freshwater resources in jeopardy. In this blog series, I hope to analyze the role of transparency, accessibility and authority within Ontario legislative tools. Here, I will seek to understand how these aspects of policy create or deter from a sense of community and appreciation of water in Ontario, and to emphasize the necessity for a stronger policy to demonstrate our interdependence with water.

Accessibility

Accessibility in policy is a key tool that provides necessary information to the public and inspires social consciousness and action. Within Canadian resource politics, it is mandated that the public be able to access key information regarding resource extraction, commodification and trading – and be able to comment on the proceedings. Nevertheless the Provincial government can create barriers to accessibility through dated search systems and political language to restrain social mobility, therefore decreasing possible public action against new permits and bills. This can be seen within the Permit to Take Water Program (PTTW) in Ontario, which sanctions access to aquatic resources for industrial, municipal and commercial use.

Accessibility is key to initiating public interest and participation within the Permit to take water program. According to both the PTTW and the Ontario Environmental Bill of Rights, every applicant for a permit must post notice of their application to affected parties of the proposal (i.e. community, nature groups, etc.) by any medium they decide - such as community notice, letter, phone call - (Environmental Bill of Rights 8(1)), in addition to uploading their application onto the Ontario Environmental Registry, an online database available to the public. After the application is uploaded, the public must have at least one month to generate feedback (8(4)), with this period being flexible depending on interest (8(6)).

Source: Emily Hines, 2015

The period of time for feedback is based solely on public engagement. As seen with Wellington Water Watchers in Aberfoyle with the Nestlé case, when there is large amount of public debate and scrutiny, the period of revisal can be extended to allow more time for contemplation and open dissent. Furthermore, according to section 90.1, the Ontario Court may dismiss an action of an applicant (such as a permit) if it is within the public interest. This was seen in Aberfoyle, with the 2013 appeal against the permit restriction in Guelph County against Nestlé. Here, accessibility is key to public awareness – and as of yet the Ontario Ministry of Environment and PTTW program is not suitably equipped for this task.

The current environmental registry in Ontario is outdated and cluttered, lacking an aesthetic ease for common readers. The search function allows for distinction of region (not county) notice type, status, instrument use keywords and dates, with options given, yet relies on an outdated layout and extensive terminology. The information is available, but not readily accessible.

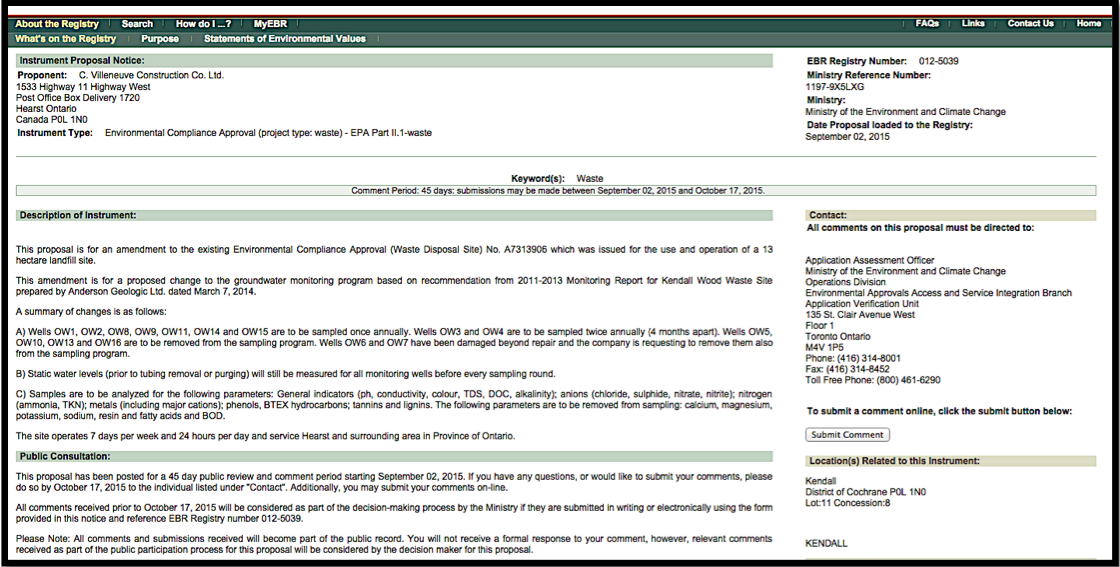

Traversing through the website is arduous, therefore losing readers through the hoards of information. When a specific application is found, the language used is that of political jargon that loses the fundamental facts and figures (for the average reader) in translation. This language can be adapted and/or simplified by the applicant at their own will, but is not mandated by the site. In the example below, the applicant - a Waste Disposal Site - uses language and measurements specific to the scientific mandates of landfills and waste disposal in Ontario. A reader without a background in politics or environmental policy is left to decipher the applications as they see fit, without the aid of definitions or links for more information. I have included a demonstrative walk-through of a sample application below.

Regarding public awareness and debate, open forums are not available through the Registry. One is only allowed to submit an anonymous comment through the website itself, if within the timespan of public awareness. The possibility for public debate directly on the registry is not given, prohibiting further discussion amongst potential connectors within the community. This secularization limits discourse between community members, politicians and non-governmental organizations at the source of the conflict, and forces discussion onto another medium. Comments are sent only to the decision makers, with no individual responses provided. They are from individual to decision maker only, with no transparency of others’ concerns or submissions.

The registry does provide the possibility to create an account with the EBR – therefore being able to ‘watch’ a number of applications, notices and approvals over a period of time. Here, notifications are sent to your email based on the applications you have flagged to ‘watch’. This encourages continuous visits to the site, as well as enabling a ‘watchdog’ like attitude for all citizens over our environment.

Ultimately, we need the information to be presented in a concise and clear format, using comprehensible language, and providing room for debate. This includes consistent measurements (i.e. maximums and minimums of takings, the use constant measurement units such as litres a day or litres an hour).

This shift from available to accessible will provide a tool for public engagement and collective action, while further sparking an interest in our local environment. Currently, businesses – such as bottling companies – rely on a lack of public interest to allow industrial growth, using aquatic resources. Through the outdated methods of information availability, we are allowing industries to monopolize Canadian water and dictate environmental policy.

We have seen in both B.C. and Ontario that social engagement can change water policy and protect the resource that binds us all to each other and the land we use. Without this, we are giving our consent to industry to continue taking our water, until it is too late.

- What has been your experience with this permit process?

- How accessible is it?

- What permit process exists in your jurisdiction of the Great Lakes?

- Why is accessibility important to you?

A Brief Walk-Through of the Registry

Search Page, collapsed

Search Menu, expanded

Latest Search Results Based on Date (September 2nd, 2015)

Example of Current Application for a Instrument Proposal

*Note that submissions (comments) may be made for 45 days.

The Description Reads:

“This proposal is for an amendment to the existing Environmental Compliance Approval (Waste Disposal Site) No. A7313906 which was issued for the use and operation of a 13 hectare landfill site.

This amendment is for a proposed change to the groundwater monitoring program based on recommendation from 2011-2013 Monitoring Report for Kendall Wood Waste Site prepared by Anderson Geologic Ltd. dated March 7, 2014.

A summary of changes is as follows:

A) Wells OW1, OW2, OW8, OW9, OW11, OW14 and OW15 are to be sampled once annually. Wells OW3 and OW4 are to be sampled twice annually (4 months apart). Wells OW5, OW10, OW13 and OW16 are to be removed from the sampling program. Wells OW6 and OW7 have been damaged beyond repair and the company is requesting to remove them also from the sampling program.

B) Static water levels (prior to tubing removal or purging) will still be measured for all monitoring wells before every sampling round.

C) Samples are to be analyzed for the following parameters: General indicators (ph, conductivity, colour, TDS, DOC, alkalinity); anions (chloride, sulphide, nitrate, nitrite); nitrogen (ammonia, TKN); metals (including major cations); phenols, BTEX hydrocarbons; tannins and lignins. The following parameters are to be removed from sampling: calcium, magnesium, potassium, sodium, resin and fatty acids and BOD.

The site operates 7 days per week and 24 hours per day and service Hearst and surrounding area in Province of Ontario”.

Questions Left Unanswered

1) Where can I access the Kendall Wood Waste Site? Why is it not attached for additional information?

2) Where are these wells? Is a map available? Why are some wells sampled annually, and others every 4 months? Why are these wells being removed from sampling – what qualifies this criteria? What caused the damage of wells OW6 and OW7 – was this a direct result of activity in the area by the company?

3) Where is the information of static water level minimums?

4) Why are we taking out the tests for these specific parameters? Are there government mandated maximums and/or minimums for each of these parameters and General Indicators? Where are these available? What defines a parameter compared to a General Indicator?

Notes on the Process

Most of the answers to the above questions can be discovered through basic research, however the information is not available directly on the same page as the application.

This makes the independent reader responsible for extra research and data collecting for complete understanding of the application. Again, all research and information is available online, but not easily accessible.

Next in this series by Emily Hines:

The Use of Authority